Unless the BBC are keeping something extremely far up their sleeves, there is no A Ghost Story for Christmas this year. This is strange, considering the strand is hardly dependent on massed crowds of extras, sex scenes, long location shoots or anything else that might cause problems for a Covid-era production. Mark Gatiss’s self-penned ‘The Dead Room‘, from 2018, would take very little reworking to be quarantine compliant.

As it is, the last of the Ghost Stories to date is Gatiss’s third entry as writer and director, as well as his second adaptation of M.R. James. In terms of the strand’s development, ‘Martin’s Close‘ is the equivalent of ending on a cliffhanger. It is, in many ways, more in keeping with the mood and style of the classic Lawrence Gordon Clark films than any of the other 21st-century instalments. This, however, begs a question which is as yet unresolved: is A Ghost Story for Christmas now purely a nostalgia product, or does it still have the potential to speak to our times in the way the 1970s ones did?

Compared to pre-Gatiss instalments like ‘Number 13‘ and Neil Cross’s ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You‘, ‘Martin’s Close‘ is laudably dedicated to the Jamesian elements that might seem hard to sell to a modern audience. It is gradually paced and single-minded, refusing to supply back-story or character arcs. Such screenwriter’s tricks would only distract from the purity of the horror, and in any case, Gatiss has a leading man who is perfectly capable of holding the attention without emotional firework displays.

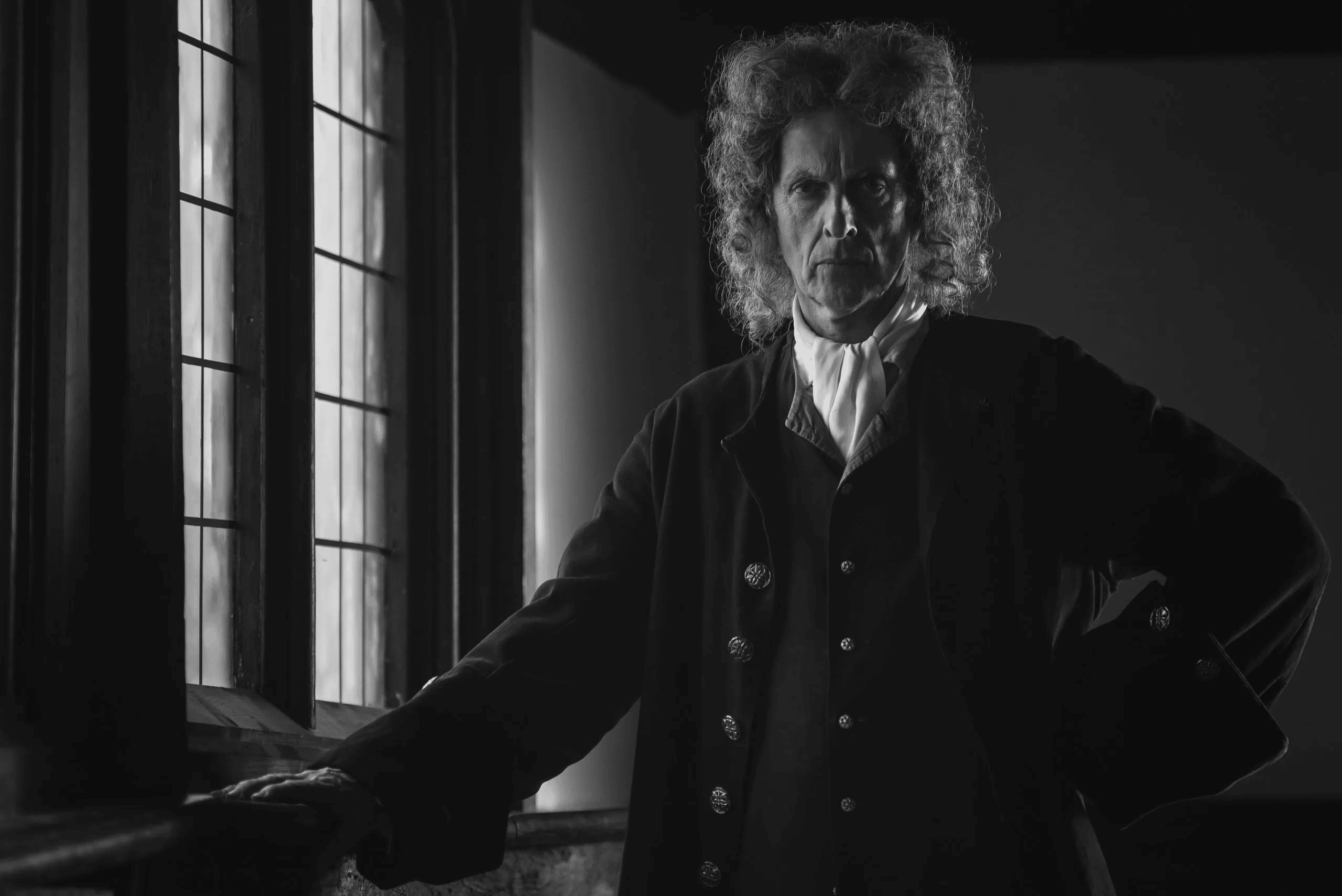

Before transmission, a lot of the anticipation for ‘Martin’s Close‘ centred around Gatiss’s reunion with Peter Capaldi, who starred in three of his nine Doctor Who (BBC, 1963-) stories. Yet as soon as Capaldi enters, it’s easy to forget his past roles and accept him as the diligent barrister Dolben. It’s strange to think of someone who has played two utterly unforgettable TV characters - Malcolm Tucker and the Doctor - as a character actor, but Capaldi is, in the best sense of the phrase. He’s the rare modern British actor who you can easily imagine in the 1950s, flitting between Hammer horrors, early Carry On films and prestige adaptations with the same level of commitment and class.

Most of the other cast members are solid enough, and Gatiss deserves credit for recognising that James Holmes - Gary’s boss in Miranda - has a perfect period drama face. Two performances proved more divisive. The first is Elliot Levey as Judge Jeffreys, the real-life justice whose string of death sentences for the plotters of the Monmouth Rebellion against King James II became notorious as “the Bloody Assizes”.

The idea seems to be to depict this historical monster as a modern populist, continually playing to his audience and making tasteless jokes at the expense of his victims. This is a promising concept, but it falls flat. Perhaps it’s because of Levey’s performance, or perhaps the distance between a fusty seventeenth-century judge and a modern media animal-like Donald Trump or Rodrigo Duterte is simply too huge for the parallel to be convincingly drawn in half an hour. In the end, it comes off as simply distracting: not grave enough for a serious horror but not funny enough for a comedy. One moment where he mocks a frightened man’s stutter recalls Simon Russell Beale doing the same thing as Lavrentiy Beria in Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin (2017). Beale’s performance, however, left you in no doubt that this was a threat, not a joke.

It’s strange that the humour in ‘Martin’s Close’ backfires, considering that Gatiss has prior form in mixing comedy, horror and the festive period. As part of The League of Gentlemen (BBC, 1999-2017), he co-wrote and starred in their infamously terrifying 2000 Christmas special. That received some complaints about a scene where Bernice, the misanthropic vicar of Royston Vasey, spoke about disabled people in a way that harks ahead to Jeffreys sneering at the “innocent, or natural” murder victim Ann Clark in ‘Martin’s Close’.

Martin’s Close caused no such controversy, which may be because people expect transgressive or uncomfortable material in a horror story. It may also be because Gatiss’s own sensibility has softened over the last two decades, or at least become more familiar as a central part of globally successful BBC hits like Doctor Who and Sherlock (BBC 2010-17). As well as ‘Martin’s Close’, Christmas 2019 also saw him co-write a new version of Dracula with Steven Moffat, and present a documentary on the history of Stoker’s novel. In the latter, he was seen having a giggly afternoon tea with several actresses who played the Brides in Hammer Studios’ vampire films.

His career trajectory looks increasingly like Alan Bennett’s - from one-quarter of a controversial comedy team to a man Francis Wheen once described as a National Teddy Bear. It is to be hoped that, like Bennett, he will become so beloved that people are shocked again at how bitter and macabre his work can be. For now, we have ‘Martin’s Close’, which replaces James’s usual coldly academic narrator with good old Simon Williams from The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971, Piers Haggard) offering the camera a slice of Madeira cake.

Williams’s role was the second one that divided audiences, although I have to say I was rather fond of it, both as a performance and as an unforced eccentricity in an otherwise straight-ahead tale. In a piece for Fortean Times issue 387, Edward Parnell noted that the original short story “turns out to be more of a traditional haunting than the majority of James’s works”, and it’s true - the ghost of Ann Clark haunts the man who killed her, much as we expect the ghost of a murdered woman to. James enlivens it with a complex narrative structure, which is presumably why Williams is here. Comparing James’s narrator to Simon Williams sat by a crackling hearth, though, points up an area where most of the modern Christmas ghost stories fall short of the 1970s run.

Parnell’s piece concerned the real-life Devonshire village of Sampford Courtenay, where James’s story is set. You can still visit the New Inn, the pub where Clark’s ghost first manifests itself. Despite this, there is very little sense of place in Gatiss’s take on ‘Martin’s Close’, especially when compared to previous M.R. James adaptations like ‘The Ash Tree’. It’s commonly said that older television is theatrical and modern television is cinematic (using, I’d say, woefully inadequate definitions of both terms, but that’s another argument). The BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas strand seems to be moving in the opposite direction, from the lovingly-shot coastal and countryside landscapes of the 1960s and 70s to a film like ‘Martin’s Close’, which has about as much exterior filming as a Fawlty Towers (BBC, 1975-79) episode.

That said, a claustrophobic feel is never a demerit for a ghost story, and Gatiss’s interiors do have an authentically cold, wintry atmosphere. The few outdoor shoots are also used skilfully. It’s well-known that, in order to be ready on time, most Christmas television is filmed in late summer, and ‘Martin’s Close’ uses this ingeniously to differentiate the flashbacks from the courtroom scenes. Looking at the living Clark embracing her killer in a verdant glade, swarming insects lit by the low evening sun, we can easily accept this as taking place at a very different time to the miserable, grey daylight of Jeffreys’ court.

The positive and negative qualities of ‘Martin’s Close‘ all ultimately come from the same wellspring. Gatiss loves M.R. James and he loves the history of these films. This can make it a rather familiar, inappropriately warm-hearted experience, but he does revel in the archaic language and academic milieu that another adapter might run from. I found it richer and more satisfying on a second viewing, even if part of that satisfaction came from wondering where the strand might go from here. If nothing else, Gatiss absolutely nails the rhythm of Lawrence Gordon Clark’s signature style of horror: a lot of suggestion, followed by something nastier than expected when you don’t expect it.

Graham Williamson

Film-maker and writer for @TGS_TheGeekShow

and @BylineTimes. Host of the Pop Screen podcast